ARCHITECTURAL ACOUSTICS

Preparing Experts for a World Growing Louder

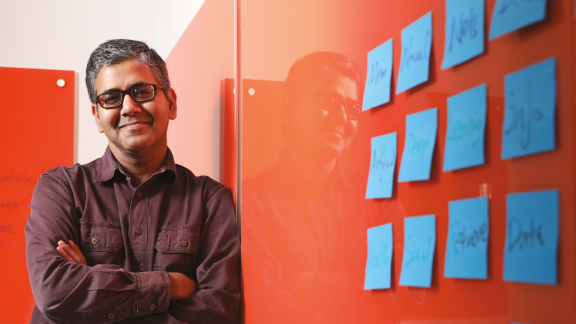

“As we have more sound and understand how to control and improve the sound, we are making a real difference in society.”

— Ning Xiang

As the world has grown louder, research scientists have gained extensive knowledge of how to improve the acoustics of interior spaces and block out the noise that hampers workplace productivity, patient care, and learning.

Rensselaer has made a significant contribution, with a world-renowned graduate program in architectural acoustics that teaches practitioners and scholars to design spaces with optimal sound quality. Established nearly 20 years ago in the School of Architecture, the program is among the most comprehensive in North America, at a time when boosting sound quality is becoming urgent.

“The need to understand acoustics is more profound than ever,” says Ning Xiang, the program’s director. “As we have more sound and understand how to control and improve the sound, we are making a real difference in society.”

A researcher, educator, and inventor, Xiang is one of just 16 individuals worldwide to win the Wallace Clement Sabine Medal, the field’s top honor. Now, he has edited Architectural Acoustics Handbook (504 pages, J. Ross Publishing), which culls the theory and applications from some of the leading minds in architectural acoustics.

The handbook, which includes information not found elsewhere, is geared for use in research, undergraduate and graduate study, and application by acoustics consultants, industry engineers, and recording professionals.

“This reference will play a fundamental role in the sustainable progress of architectural acoustics research and practical applications,” according to J. Ross Publishing. “World-renowned experts in the field from both the research and consulting communities contributed to the 15 chapters covering a wide range of sub-fields including computational modeling, noise, vibration controls, and environmental acoustics in the built environment and around buildings.”

The architectural acoustics program Xiang heads at Rensselaer has educated more than 130 specialists who collaborate on the world’s great concert halls, libraries, airports, corporate headquarters, and university venues. Graduates also help boost health care, education, and workplace productivity by assuring that people in these settings hear the critical information — and not the unwelcome, distracting noises.

Rensselaer students also learn psychoacoustics — how humans perceive sound. The program is currently using a National Science Foundation grant to research how the brain decodes sound.

“In architectural acoustics we are dealing with two sides: the beauty of the sound and the ugly of the sound,” notes Xiang. “Back in the 1960s, noise level averaged 60 or 70 decibels. Now one finds easily 90 or even 100. You have to get rid of the ugly side of the sound if you’re near a highway or an industrial operation, where a lot of activities are.”