Creating the Crossroads for Climate Innovation

The new Institute for Energy, the Built Environment, and Smart Systems will drive collaborations to build a more sustainable world.

By Reeve Hamilton

On the morning of April 23, 2021, two particularly pressing emergencies were top of mind for world leaders: the global climate crisis and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. To address the former, President Joe Biden was hosting an unprecedented Leaders Summit on Climate.

The prominence of the participants underscored that a more sustainable future is truly a global priority. According to the White House, it was the largest virtual gathering of world leaders, with 40 heads of state invited from around the globe, along with a handful of the world’s foremost leaders in business and public service.

“Raising our innovation is what is going to make it possible to raise the world’s climate ambition,” U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said as she introduced a panel of speakers during the morning’s opening session. Titled “Unleashing Climate Innovation,” the session included remarks from Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry, U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates, and others. In her remarks, Secretary Raimondo noted that the government cannot address climate change on its own. Along with entrepreneurship from the private sector, she said, “We need academic research institutions to play a huge role in uncovering and developing new technologies and innovations.”

While the critical importance of academic research was mentioned a number of times, among the speakers Raimondo was about to introduce — in fact, out of all of the participants in the entire summit — there was only one university leader: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute President Shirley Ann Jackson.

“Universities are the crossroads for collaboration across disciplines, sectors, geographies, and generations,” President Jackson told the summit attendees. “An integrative approach is required to decarbonize the many interconnected systems of our daily lives.”

President Jackson offered details of how Rensselaer is leading the way, and officially announced the formation of the new Rensselaer Institute for Energy, the Built Environment, and Smart Systems — also known as EBESS. In the nearly two centuries of Rensselaer history, perhaps no research center has ever been launched on as global a stage as this one.

With the world’s leaders tuned in, President Jackson explained how EBESS, which will be based in New York City, will “use the most advanced digital technologies to drive decarbonization of urban environments at the systems level,” how it will “model integrated transportation, communications, and supply chain networks,” and how the work it produces will “create infrastructure that is both net-zero in energy use and climate resilient.”

Fatih Birol, the executive director of the International Energy Agency, spoke immediately prior to President Jackson, and he noted that roughly half of the technologies needed to reach net-zero by 2050 have not yet been developed. However, in her unveiling of EBESS, President Jackson discussed where some of the key innovations and necessary technological strides would be made. “EBESS will link architecture design, engineering, and a new approach to regulation,” she explained. “EBESS will also use new materials, renewable energy systems, and sentient building platforms to maximize human health and well-being.”

EBESS Leadership

Collaboration across disciplines that accelerates both academic and research progress is a hallmark of Rensselaer. EBESS will thrive at Rensselaer because such an approach is endemic to the university.

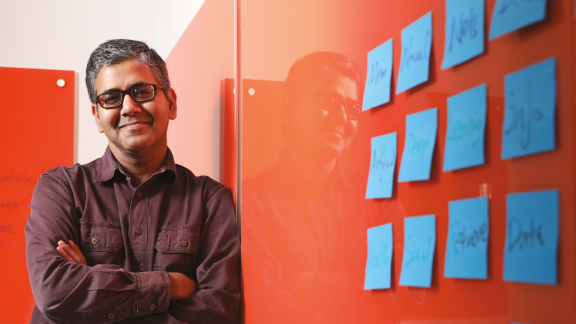

The opportunity to work in an environment with such low walls between disciplines — coupled with the rich legacy of world-changing research at Rensselaer — is what first attracted Dennis Shelden, a prominent architect, entrepreneur, and author, to join Rensselaer as the director of the Center for Architecture Science and Ecology (CASE) in 2020. Shortly after arriving, he explored collaborations with Bob Karlicek, the director of the Lighting Enabled Systems & Applications (LESA) Center. The two were named co-directors of EBESS, and their respective centers will collaborate with many other centers and schools across Rensselaer, as well as with industry partners and other universities.

“With the proven leadership and expertise of Dennis Shelden and Robert Karlicek, this new institute will accelerate the innovation of climate-friendly environments around the globe,” President Jackson said in her announcement.

Shelden previously spent 17 years as an associate of legendary architect Frank Gehry. In 1997, he joined the firm Gehry Partners, where he was responsible for the management and strategic direction of the firm’s computing program, including software and process development. In 2002, he cofounded the spinoff company Gehry Technologies, serving as chief technology officer on the development of several software products, and project executive on numerous groundbreaking building projects until the firm’s acquisition by Trimble in 2014. He has held teaching positions at multiple academic institutions, including MIT and Georgia Tech.

Karlicek, meanwhile, is a well-known LED — light-emitting diode — industry expert. He spent over 30 years in industrial research and management positions with a range of corporations, including AT&T Bell Labs, EMCORE, General Electric, Gore Photonics, Microsemi, Luminus Devices, and SolidUV before joining Rensselaer, where he also serves as a professor of electrical, computer, and systems engineering.

“I think it’s critically important that we realize that buildings still have a lot of work to do to be much more energy efficient and reduce their overall carbon footprint,” Karlicek says. “And I think Rensselaer — through CASE, LESA, and many other research platforms across campus — has been at the forefront of leading change in this direction for a long time.”

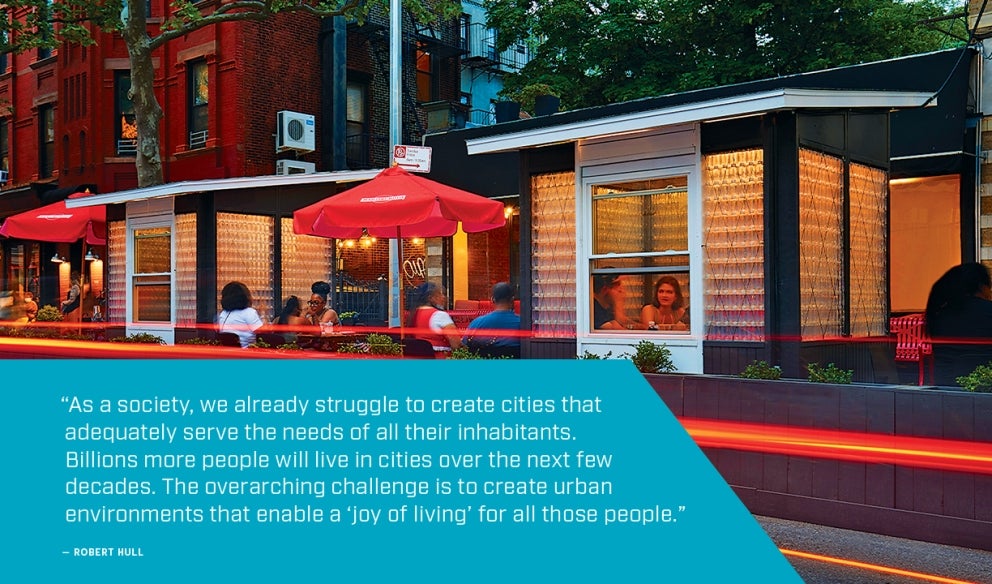

“As a society, we already struggle to create cities that adequately serve the needs of all their inhabitants,” says Robert Hull, acting vice president for research at Rensselaer. “Billions more people will live in cities over the next few decades. The overarching challenge is to create urban environments that enable a ‘joy of living’ for all those people.”

Primarily located in New York City, CASE has driven collaborative innovation in sustainable architecture and the built environment for more than a decade. LESA is a graduated National Science Foundation Engineering Research Center dedicated to developing autonomous intelligent systems to address modern challenges in the connected environment.

“If you look at the agenda of CASE, which is very much about designing building-level problems and environments, and the ambitions of LESA, which has focused more on the kind of technologies that go into a building and making a building smarter, there’s an obvious synergy between those pieces,” Shelden says.

The Big Picture

Industry and real-world engagement is a critical part of EBESS’ strategy for realizing the impacts of its research. EBESS was launched in initial partnership with Siemens, Lutron Electronics, Brooklyn Law School, the building engineering consulting firm Thornton Tomasetti, and the international architecture firms HKS, OBMI, and Perkins&Will. It will also integrate research across many centers and schools at Rensselaer, including the Center for Materials, Devices, and Integrated Systems (cMDIS), the Center for Future Energy Systems (CFES), the Center for Infrastructure, Transportation, and the Environment (CITE), and the Institute for Data Exploration and Applications (IDEA).

“I think that we are going to see a renaissance in the built environment in terms of how we make buildings sentient and how that building awareness delivers more human-centric, energy-efficient services,” Karlicek says. “For instance, I think we are going to redefine how electricity and data are distributed in a building to make it more efficient and aware of occupant needs.”

The growing list of partners will be tackling a range of problems as complex and multifaceted as the cascading consequences of climate change. For example, Brooklyn Law School will be examining regulatory frameworks and how they can better enable the development of net-zero buildings. Elsewhere within EBESS, researchers and industry leaders might explore how new materials and sentient building platforms can be utilized to maximize human health and well-being. Shelden describes EBESS as an opportunity to scale both up and down — “down to small-scale devices, and up to cities and even country-level involvements.”

Industry input is particularly critical for ensuring that some of the big dreams energizing the research remain grounded in reality and that the designs and innovations can fit together out in the world and be effectively implemented.

“Coupling institutional knowledge with industry knowledge hopefully can yield to greater and deeper studies that will help reverse climate change and address embodied carbon issues,” Charlie Portelli, architect and computational designer for Thornton Tomasetti and adjunct professor at CASE, told Engineering News-Record following the announcement of EBESS. “Working with academia, we want to share this industry knowledge and thought leadership on performance-based design and decarbonization efforts in the built environment.”

In addition to developing new technologies and strategies for building infrastructure and environments, the work of EBESS will naturally lead to the development of new and integrated ways of teaching subjects relevant to building a more sustainable world.

“I think it’s really going to be exciting to take a look at how we teach architects about detailed aspects of machine learning, sensor system design, and distributed intelligence,” Karlicek says, “and at the same time, have architects teach engineers about concepts of design and ergonomics and how people use spaces. These barriers aren’t really crossed all that often, but creating a pedagogical environment where architects and engineers speak the same language is going to help us make significant progress.”

In many ways, EBESS is the embodiment of The New Polytechnic, a paradigm that enables collaborations between talented people across disciplines, sectors, and global regions, in order to address the complex problems the world faces.

It’s clear the solutions capable of addressing the nuanced challenges facing the world — re-envisioning and designing integrated building environments for human well-being and sustainability — requires a platform as bold and nimble as EBESS.

“Humanity isn’t done growing,” Shelden says. “There will be more people on the planet, and we have to double our capacity while reducing our footprint by half. How do we do that? How do we do more with less? EBESS can be a great part of defining those answers and developing the solutions.”

Spotlight: Mia Rogers ’20, M.S.’21

Through studying abroad in Latin America while earning her undergraduate degree, Mia Rogers ’20, M.S.’21, grew her passion toward urban design with a focus on utilizing design as an advocacy tool for disadvantaged communities.

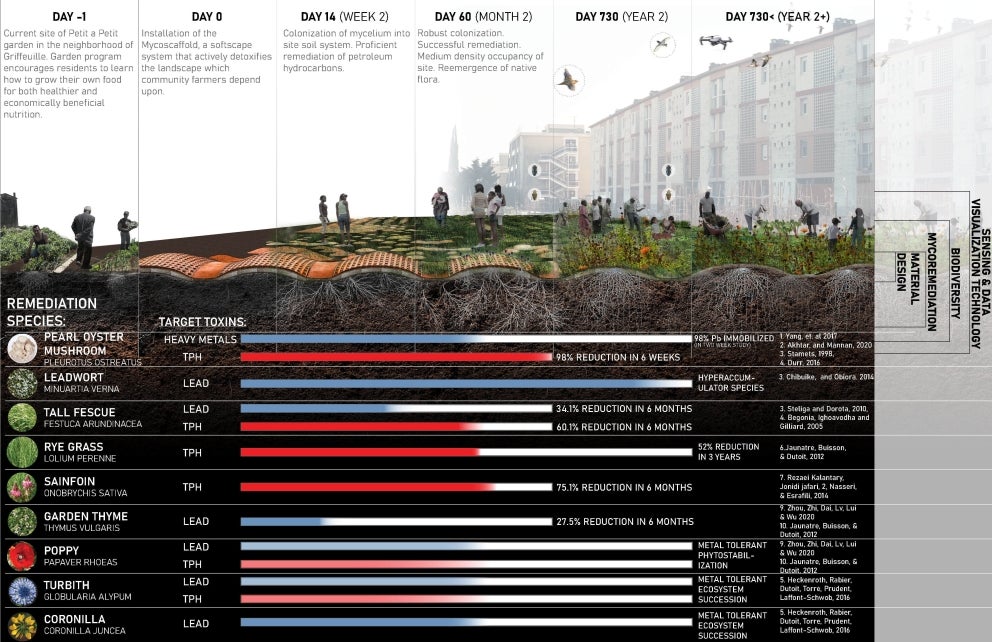

This drive behind her design motivated her to pursue her thesis in the Built Ecologies program. The proposal focuses on the tailoring of the mycelium remediation technology system to the community of Griffeuille in Arles, France, where the design will present a means to the establishment of a socially and ecologically healthy space for community members and living organisms in the local biosphere.