Tapping Into The Brain

Exploring the inner workings of the human mind.

By Regina Stracqualursi

Our brains control everything we do each day. From the involuntary actions that keep us alive, such as breathing, to the cognitive processes we rely on to grow and reach our full potential, such as learning, our brains are responsible for it all.

While the brain is so critical to everything we do, much about the complex organ remains unknown. Faculty at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute are at the forefront of an ever-growing body of research that seeks to understand how the brain works in order to tackle critical issues head-on.

Improving Surgical Training

A research team from the School of Engineering, in collaboration with the University of Buffalo, is on a mission to improve surgical training and skill assessment and, ultimately, make surgery safer as a whole. To do so, with the support of a $2.2 million grant from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command of the U.S. Department of Defense, the researchers are turning to the brain — using neuroimaging and neuromodulation — to better understand and measure the skills that surgeons acquire.

“Being able to improve technical skills and certify surgeons based on quantitative metrics is an absolute necessity for a safer surgical environment,” says Suvranu De, head of the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Nuclear Engineering and co-director of the Center for Modeling, Simulation, and Imaging in Medicine (CeMSIM) at Rensselaer, who leads the research.

Currently, surgical skill assessment in the United States is based on the speed at which a surgeon completes a procedure in combination with the number of errors made. By looking directly at what is happening in a surgeon’s brain via neuroimaging, however, the researchers can not only tell a surgeon’s skill level, but also predict the score they will currently receive based on time and error, through the use of artificial intelligence.

“The brain patterns of someone who started as a novice who moves to an expert level will change,” says Professor Xavier Intes, bioimaging expert co-leading this effort and co-director of CeMSIM. “By monitoring the cortical activation of the brain via optical methods, we can gain insight into the mechanism of surgical skill acquisition and execution.”

In addition to understanding and measuring surgical skill training, the team is also investigating how to improve it with neuromodulation, which provides a small electrical current via electrodes on the brain while surgeons are performing technical tasks. “What we see is that the brain patterns are different between periods of activation and no activation,” says Intes. The preliminary findings have shown promise in using such technology to reduce errors in surgical performance.

Combating the Effects of Stress

Alicia Walf, neuroscientist and senior lecturer in the Department of Cognitive Science, has been studying the brain for over 20 years. After dedicating her early career to understanding the actions hormones take in the brain and the mechanisms of structures within the brain, she’s spent the last decade looking at the impact of stress on cognitive functions.

“Some of the effects of short-term stress are helpful,” Walf says, citing temporary benefits such as improved focus and attention. “But when we think about the long-term effects, they are not healthy for our bodies or our brains.” Chronic stress not only results in physical changes to the brain, such as a loss of brain cells, but also behavioral changes, such as changes in memory, emotional processing, and focus. “If you’re refocusing on stress over a long period of time, you’re missing out on other things that are going on,” says Walf. “This is when people feel like they’re distracted, are more likely to feel confused, or are not able to focus when they have to, like in the classroom or at work.”

Aside from understanding the effects of stress on the brain, Walf’s work focuses on combating it. In recent years, she has led initiatives on the Rensselaer campus aimed at helping students, faculty, and staff understand and foster well-being. “Stress can’t really be avoided so the focus becomes finding ways to effectively deal with it,” says Walf. “Actions to reduce stress are not just a one-time thing — the benefits come from sustained practice.”

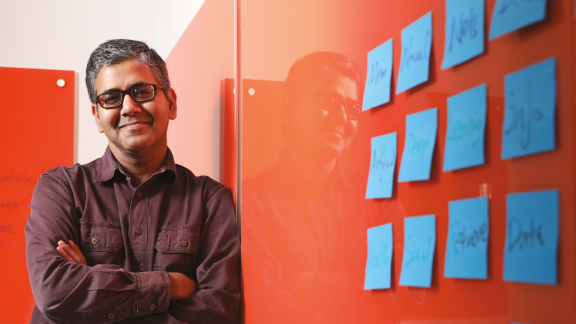

Identifying Cognitive Biases

Gaurav Jain, assistant professor of marketing in the Lally School of Management, is fascinated by human behavior. His research specifically focuses on identifying cognitive biases in consumers and understanding how those biases influence final decisions.

In one recent study, Jain and his collaborators from Manhattan College and the University of Iowa re-examined fluency, a phenomenon that has been studied by marketers, psychologists, and economists for decades. Traditional fluency literature states that if something is more fluent, or easy to understand, people will like it more. However, the researchers found that this isn’t always the case. “If a message is more disfluent, people will spend more time making a decision,” Jain says. “If they spend more time, they will like their decision more.”

Another study revisited attribute framing, which has traditionally focused on the words used to describe what’s being measured, such as the words “fat” and “lean” on a package of ground beef. Jain and researchers from the University of Iowa found that people have a preference for round numbers even when the non-round, specific number is better news. So if someone interested in eating healthy picks up a package of ground beef that is 92.5% lean, they will likely think the beef is less healthy than if the beef had been 90% lean. “When it’s a specific number, people think about it,” Jain says. “Human beings have a need for cognition — if something catches our attention, we have to explain it.”

While Jain studies human behavior in relation to consumption, the applications of his research go far beyond that. “This work can be used to create more persuasive messaging,” says Jain. “For instance, it has direct implications to discourage people from using products that are not good for their health, such as cigarettes.”

Understanding Decision-Making

As a behavioral and experimental economist in the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, Assistant Professor Ian Chadd works to understand what influences the thousands of choices we make as humans. Whether making small decisions, such as what laundry detergent to use, or large decisions, such as what type of car to drive, we constantly seek information to help us make the best choice possible. But what happens when we review information that is not relevant to us or options that are no longer available? In the example of choosing a car, this could include details about features you won’t use or models that are out of stock.

While it has been commonly thought that irrelevant information and unavailable options are easily ignored by consumers, a study conducted by Chadd, along with researchers from the University of Maryland, revealed that their presence ultimately makes people worse at making decisions. “Seeing irrelevant information or providing irrelevant information to a consumer is not a costless action,” says Chadd. “In the presence of natural cognitive constraints, the abundance of information can have a hidden downside.”

The findings are important for both decision-makers and those presenting information to a specific audience. “Pointing out where those downsides exist is important as we design systems to make new information available and navigate a world with an abundance of information that may or may not be relevant to us.”

Looking to the Future

“We still have a long way to go,” says Walf, regarding our knowledge of the brain. Despite all that has been learned in recent years, there is still much to be discovered. Collaborative research in this field will be key to advancing human health and well-being — from understanding the mechanisms behind the neurodegenerative diseases affecting millions worldwide to the cognitive processes that drive our behavior.

Related: Gaurav Jain and Ian Chadd discuss their research on Why Not Change the World? The RPI Podcast.