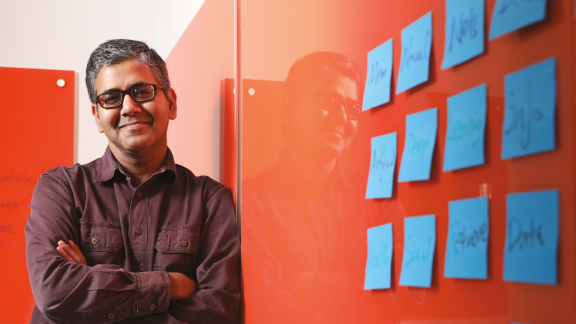

The Homecoming of Martin A. Schmidt ’81

As he returns to lead his alma mater, President Schmidt reflects on where he’s been, and where we might go together.

By Christian TeBordo

The first thing you should know about Martin A. Schmidt ’81, Ph.D., 19th president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, is that everyone on campus calls him Marty. The second thing you should know is that he never actually planned on being a university president.

“I know a lot of people who have a vision of where they want to go that’s very long term and very forward thinking, and everything they do builds on that,” he says.

In contrast, Schmidt’s whole career has been guided by intellectual curiosity. “I was always seeking that level of interest that motivates me to do things really hard and spend a lot of time on them, just because I’ve got a passion about it.” Even as provost at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he was driven by the challenge and stimulation of the position, rather than opportunities for advancement. “I felt like when I reached the point of ‘been there, done that’ with being provost, I would step down and reactivate my research and teaching.”

In person, it’s clear he means every word of this. He’s warm, expansive, charismatic, and deeply curious — all, paradoxically, good qualities for a university president. Which raises the question: How did he end up here?

A Natural Fit

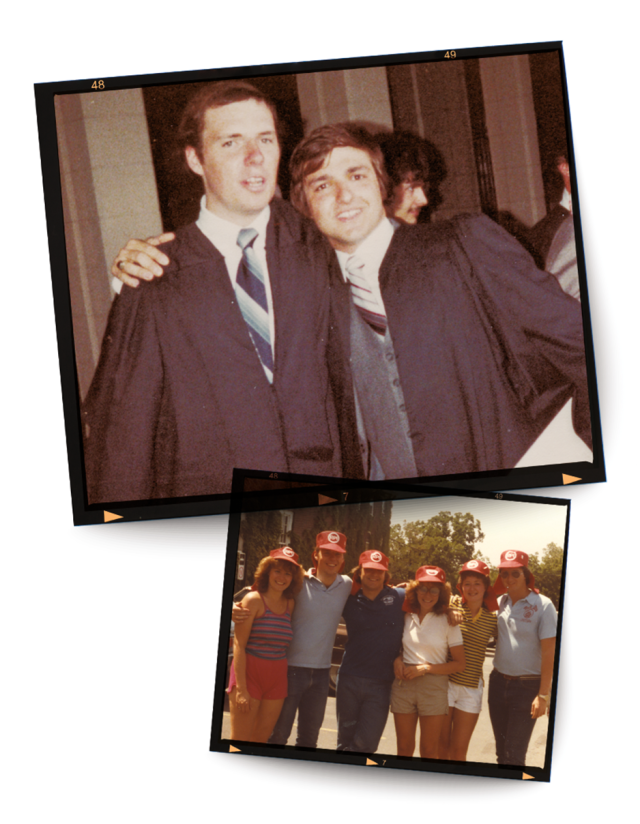

To answer it, you have to go back to the fall of 1977, when he first arrived on campus. Asked why he chose to attend RPI, he says, “It’s very much an instinctive thing,” and then illustrates with a story about his third son, Kevin.

Kevin had been accepted to several schools, and together, father and son toured them. One campus struck Schmidt as particularly dreary. It was March in rural New England, a muddy, slushy time of year. “I was thinking it was going to be a short trip,” he says. “We’ll be back in Boston in four hours.”

But at the end of the tour, Kevin turned to him and said, “Dad, I definitely see myself here. I had a great time.”

That was the same feeling Schmidt had visiting RPI. “It felt comfortable, like this was a place where I could be successful. Of all the campuses I visited, this is the one that felt like a natural fit.”

It also helped that RPI offered top-tier programs in both engineering and architecture, the two fields he was considering at the time. What he knew was that he wanted to design and make things. As a high schooler he’d enjoyed working on cars and building furniture. If it seems like that would give architecture the edge, you’re not seeing things the way Schmidt sees them.

He was starting his studies just as computing was moving from mainframe to personal, and the moment he discovered microelectronics, he realized the field was full of opportunity. The deeper he drilled into semiconductors, the more possibility he saw. “There was a tradition of making computer chips,” he says, “but what was emerging was a field that was taking those manufacturing techniques, which are fundamentally ways of making very small things, then applying them to things that are non-electronic.”

After completing a bachelor’s in electrical engineering at RPI, he continued on to MIT, earning a Ph.D. before joining the faculty there. And all along, his interest in building small things that make a big impact adapted and changed. Accelerometers and gyroscopes. Sound and motion sensors. As the technology evolved to the point where you could manufacture devices as small as a human cell, he moved on to biological, and then chemical, applications.

Even now, after 11 years as an administrator, he wears his passion for science and collaboration on his sleeve. When you mention, for instance, the research and manufacturing activity on micro- and nanotechnology going on in the Capital Region, and how that could benefit from the recently passed CHIPs and Science Act, he positively lights up. “This is an enormous, enormous opportunity, and as someone who grew up in this field, I’m just thrilled that the U.S. government came together in a bipartisan way on this issue.”

From there, he launches spontaneously into a history of chip manufacturing; the importance of re-shoring the industry for the sake of innovation, the economy, and national security; and how, if all of the local private, public, and higher education players work together, “we’ll have a transformative impact on the region that will last long beyond my tenure as president of RPI.”

It’s the perfect field for someone who is always on the lookout for new challenges. Over decades of teaching and research, he was issued more than 30 U.S. patents and founded or co-founded seven startups.

But Schmidt also has a good sense of when it’s time to hand the reins to someone else and move on to something new. This allows him to accomplish more, and create more opportunities for others, by working from a secure foundation. For example, when spinning off a start-up out of his lab, Schmidt would identify people, typically current or former students, and recruit them as leaders for these fledgling organizations. Then he would hire seasoned executives and provide support as a consultant while moving on to his next research enterprise.

“Stepping away from things gives you new perspectives,” he says. “My Ph.D. adviser at MIT always told me that everybody is capable of good work. What differentiates them is the selection of problems they choose to work on.” So when he was offered the position of associate provost at MIT, and then later provost, he accepted the challenge.

New Habits of Mind

As an administrative leader, his background in engineering came in handy. He mentions discussing a problem that had caused trouble across the higher education industry with a group of fellow provosts from other schools. One of them pointed out that MIT had handled the issue very well, and asked Schmidt how they had done it. Schmidt explained how his team had used data and analysis to arrive at their solution, leaving the other provosts vocally wishing that they, too, worked at STEM-centric institutions.

But Schmidt cautions that engineering education doesn’t always put enough emphasis on the human element. This way of thinking has its roots in a literature course he took at RPI. “Students who come to places like RPI or MIT are often laser-focused on STEM in high school,” he says. “And when they get to college they continue with that focus. But then all of a sudden, they start taking humanities and arts courses, and a light goes on. Personally, I realized I had just been checking boxes to get where I was. Suddenly I appreciated how it all fit together.”

He got the chance to put this thinking into action when he oversaw the founding of the Schwarzman College of Computing. By MIT’s own accounting, this was the most significant structural change to the school in nearly 70 years. Logistically, he had plenty of occasion to utilize his background in engineering, and, it being a computing school, he drew on his discipline-specific knowledge when conceiving of the curriculum. But Schwarzman wasn’t meant to be a standalone program; Schmidt conceived of it as a connective tissue for the entire MIT community. “I had the sense that we could do better in the way we trained scientists and engineers so that, in the course of their work, they were contemplating the social and ethical implications of what they were working on,” he says.

In order to do that, he set out to cultivate new “habits of mind,” a phrase he learned from his then-colleague Melissa Nobles, who is now the chancellor at MIT.

It’s easy to require every student to take an ethics course, but there’s a risk that it will become a mere formality and fade in the rearview. “By cultivating ethics as a habit of mind, you can infuse all aspects of teaching and learning with the human context and social implications of research,” he says.

This, too, has carried over into his presidency. While his passion for semiconductors makes it clear he has big ideas and the energy to act on them, his very first initiative as president is what he’s calling a “listening and learning tour.” “I want to maintain an open mind,” he says.

The listening part of the tour consists of hour-long, small-group meetings with students, faculty, and staff. Learning refers to deep-dive visits at each school of the Institute, following the deans to get an idea of daily life in each program. What’s emerging is a sense of opportunity as expressed by the community itself.

“There are two questions I won’t let anyone leave the room without answering,” he says. “What do you love about RPI? And what are your aspirations for the school?”

His conclusion? “People love RPI. They’re here for a reason. It’s not all puppies and sunshine, but we have a phenomenal foundation on which to build, and I’m grateful for the work that President Jackson did to set that foundation.”

Arthur F. Golden ’66, JD, Chair Emeritus of the Board of Trustees, says, “Marty’s status as an alum, coupled with his entrepreneurial, research, and academic career experience and accomplishments, makes him a perfect fit with RPI’s culture, alumni/ae groups, and my and the Board’s ambitions and expectations for where he will take us as RPI continues its upward trajectory. He believes in, and shares, our dedication to providing education to the broadest possible array of top-quality students, and nurturing a collaborative faculty to enhance their research and development contributions to industry partners and, generally, to science and engineering. That was my belief ever since the first afternoon we spent together a year ago as the search process for the 19th President of Rensselaer was about to begin. The past year has made me even more confident of my initial assessment of him as a unique person, the next leader for RPI, and as a partner for the Board. I am confident he will lead RPI to new heights in all areas.”

Answering the Call

Which brings us back to how Martin A. Schmidt – Marty – ended up returning to Rensselaer after 41 years. In higher education, a provostship is often looked at as a stepping-stone to a presidency, and a provost who helped found a new college at MIT would be highly sought after by search committees.

His wife, Lyn, also considered him presidential material. “The first time I thought of Marty actually being a college president was while in grad school at Boston College,” she says. “We were dating, and I had just spent the weekend with my BC roommate, Ann, visiting her family in New Jersey. Her father, Dr. Elliott, was president of Ryder College. After spending time with the family and talking to Dr. Elliott, I came back to Boston and told Marty he’d be a great college president. He just laughed and said ‘no!’”

But as Schmidt’s career advanced, the prospect of a presidency came up again, this time with a twist.

“About 15 years ago, Marty was talking about RPI,” Lyn says. “And I said, ‘I can still see you as a college president.’ He still said, ‘No, I love teaching.’ That’s when I told him, ‘OK, but if you ever do get a call from RPI, promise me you’ll seriously consider it!’ And he agreed.”

And then, in the summer of 2021, RPI called.

“Our Presidential Search Committee, and supporting search firm, quickly identified a list of leading candidates. Marty Schmidt was among the very top candidates that we wanted to proactively reach out to, and so I personally called him to encourage him to enter the process,” says current Board Chair John E. Kelly III ’78 G, ’80 Ph.D. “As a committee, we became even more impressed with his knowledge and leadership abilities as we went through the process, concluding with recommending him to the full Board.”

Schmidt took the call, but still, he was reluctant. “I was feeling pretty comfortable where we were. We had a beautiful home in Gloucester and life was good. I couldn’t come up with anything that would be more appealing to me than what I was doing and what I planned to do when I stopped being provost.”

Lyn reminded him of his promise, and he kept his word. One weekend in September, before applying for the position, they took a road trip. It was nothing formal; they just wanted to explore. “We were walking around campus, walking around downtown Troy,” he says. “And every step of the way, the momentum built.”

He was getting excited again, ready for a new challenge.

“It’s impossible to explain how emotionally compelling this is for me,” he says. “It’s an opportunity to come back to a place that sent me on a journey I could never have imagined. I’m so grateful for the chance to help create a better RPI for the next generation of learners.”