Level Up For Health

No longer just for entertainment, video games tackle health problems head-on.

By Regina Stracqualursi

Time and time again, video games have proven themselves effective in capturing the attention of the masses. From the summer of 2016, when frenzied Pokémon Go fans traveled near and far to capture the most exotic creatures to the Fortnite “craze” of 2018, which, according to Nielsen’s SuperData Research firm, resulted in more annual revenue than any game in history, the immense power that video games hold has become clear.

While video games were once associated with leisure and entertainment, their ability to motivate and engage people led to several decades of experimentation in using gameplay in the field of education. Today, that experimentation still continues, and the idea of using games for learning is rapidly evolving and expanding to other industries. “Right now, we’re in kind of a renaissance of games for learning,” says Ben Chang, professor and director of the games and simulation arts and sciences program. “There’s a new focus on the quality of gameplay, the way that we think about game design, and ultimately, deeper thinking about the way people learn.”

One area video games have taken by storm is the health-care industry. Health professionals are now partnering with game developers to leverage technologies that have the potential to solve some of today’s most pressing health challenges. From rethinking the way doctors are trained, to developing more effective medical treatments, there is a great amount of work underway in the industry to improve the health of current and future generations.

Enhancing Medical Training

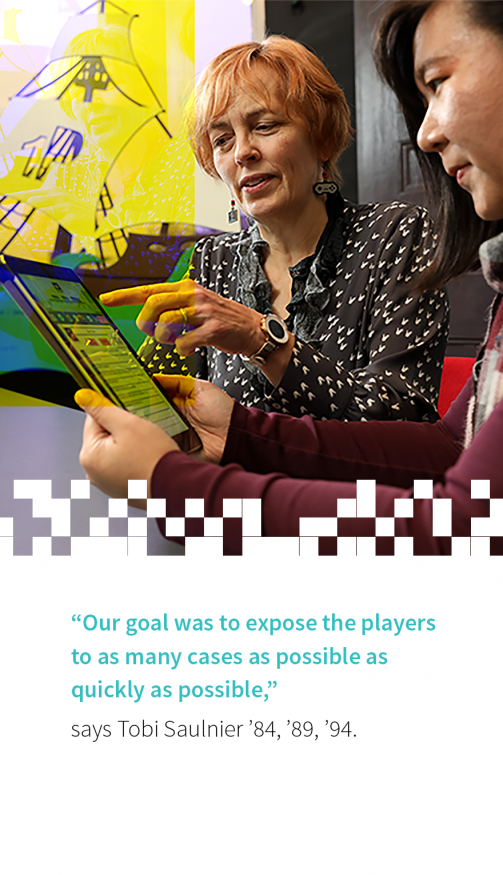

As the old saying goes, “practice makes perfect.” But what happens when practice isn’t an option? Medical students and doctors know this feeling all too well as they make hundreds of decisions a week with real lives on the line. Luckily for them, video games, and the alternate realities that accompany them, provide a safe space in which to learn and enhance their skills. SHIFT: The Next Generation, a video game developed by 1st Playable Productions, a Troy-based game development studio founded by Tobi Saulnier ’84, ’89, ’94, provides medical students and doctors with the opportunity to do just that.

The game, the result of a collaborative project supported by the National Institutes of Health with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), focuses on training emergency room doctors to prevent unnecessary deaths by more quickly sending ER patients to trauma centers. As soon as they hit play, the physicians are instantly transported into an emergency room. However, unlike the environment they experience in their day-to-day lives, this emergency room allows them to train without consequence and exposes them to a more diverse set of patients and conditions. Players are quickly presented with a series of patients they must assess while they race against the clock to decide whether or not they need more intensive medical care. “We’re trying to train them to quickly identify the reasons you would just drop everything and get a patient to the nearest trauma center,” says Saulnier. “That in itself could save thousands of lives.”

The game, tested among a group of 100 doctors at UPMC, is just one example of how video games could be integrated with traditional approaches to medical training. While other video game genres were considered by the development team, it was ultimately decided that a simulation game would be most effective. “Our goal was to expose the players to as many cases as possible as quickly as possible,” says Saulnier.

Educating Doctors Through Fiction

While realistic video games have a more obvious application for training in the health-care industry, fictional games have found a place as well. As part of a National Institutes of Health grant, game developers from Rensselaer have been working with doctors, faculty members, and graduate students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai to develop a video game that can be used to teach medical students about the process of inventing new drugs and therapies. However, instead of a game that places students inside of a lab or hospital, this one takes them to an exotic island.

When the Rensselaer team first began the project four years ago, they imagined that a video game of a serious nature would require a serious setting and narrative. However, conversations with medical students at Icahn quickly changed that. “The really key thing was bringing students into the process,” says Chang, the Rensselaer lead on the project. “One of the most striking things they told us was, ‘Look, we’re dealing with real death and disease every day. We’re doing rounds, we’re doing rotations, and we don’t want to go home and play a video game that’s exactly like that.’”

Cure Quest places medical students on an island plagued by a mysterious disease that causes people to sneeze so violently they break out in feathers. To win the game, players must identify the illness, “trans-featheration,” and find a way to cure it. While the concept might seem silly, as medical students travel to different parts of the island, they learn about the stages of the drug discovery and development process in a more lighthearted way than any textbook could accomplish. The idea that students can be entertained while also learning new material is something the researchers hope can build upon current approaches to medical education and training. “Some of what medical students deal with is really emotional — there’s an intensity to being in an emergency room, to talking with a cancer patient about their choices for entering a clinical trial or not,” Chang says. “Being able to get a little removed through fictionalization and getting out of the life-and-death stakes is actually an incredibly valuable thing for them.”

Improving Patient Experiences

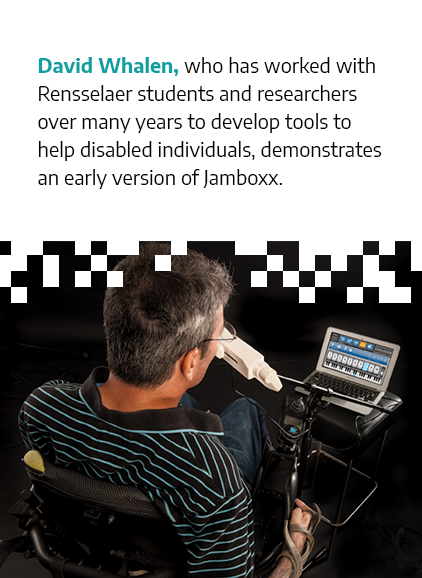

David Whalen was just 19 years old when a tragic ski accident left him paralyzed. A formal diagnosis of quadriplegia changed his life forever and took away his ability to participate in many of the activities he enjoyed, such as running and playing tennis. In 2007, after developing a breath-powered device that could act as an instrument, he and Mike DiCesare co-founded a company called My Music Machines Inc. to provide everyone with equal access to music.

Whalen, who had a tendency to neglect the breathing exercises necessary to maintain his health, found that using the device, now called the Jamboxx, had a therapeutic effect. “We noticed that when he played the Jamboxx, he was getting in a lot of breathing exercises naturally, so our thought was, ‘What if we created a device specifically to help you do your breathing exercises that was fun and provided an incentive to do so?’” says Dwight Cheu, CEO of Jamboxx.

The team set out to develop a solution that could ultimately replace the incentive spirometer, a respiratory therapy device typically prescribed to patients who have undergone a surgery or suffer from a chronic disease to prevent them from developing pneumonia. “If you go to any ICU across the country, you’ll see these devices being given out, but if you ask any of the health-care providers, they’ll tell you unanimously that no one ever uses them,” says Cheu. “They’re very tedious to use and our goal was to put the incentive back into the incentive spirometer.”

After receiving a $2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to develop a video game-based respiratory therapy device, Cheu also partnered with Saulnier, who has personally experienced the daunting task of using an incentive spirometer, and was inspired by the thought of developing a game that would have a real quality-of-life impact. “When you’re in those situations, you have to do these lung exercises even though you feel like you can’t even take a breath, let alone hold it as long as you should,” she says. “The trick is to find gameplay mechanics that make it entertaining and distract you from the difficulty and discomfort.”

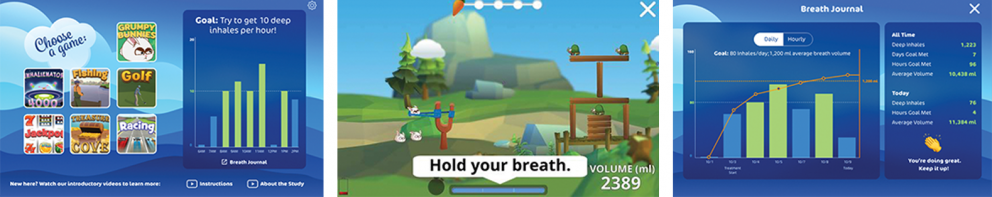

The game, ZEPHYRx: Breathe Easy, includes a suite of “minigames” designed to engage users of all ages, as individuals in need of respiratory therapy can range from young children battling cystic fibrosis to older, postoperative patients. Over the last two years, it has been used by almost 300 patients at Albany Medical Center as part of a clinical trial. As patients fill their lungs and hold their breath, they are motivated by tasks like playing a slot machine or fishing. The hope is that the interactivity of a game will serve as a distraction from the discomfort of the therapy. “There are numerous studies that show that when you’re playing video games, your pain tolerance goes up,” says Cheu. “So patients playing the game actually do their exercises more frequently and for longer durations.”

Increasing Access to Mental Health Treatments

Despite the fact that mental illnesses affect millions of people living in the U.S. each year, only about half of them receive treatment, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Whether for financial reasons or hesitation stemming from the stigma associated with mental illnesses, there is a large number of people living with a mental disorder without any way to cope with it. Queenship Game Studio, LLC, a Troy-based game development studio that launched in 2018, is tackling this problem as one of very few studios dedicated exclusively to producing games about mental health. “The mental health crisis is a global phenomenon,” says Muse en Lystrala, the company’s executive director. “The biggest problem is not necessarily the stigma, it’s the lack of access to clinically informed tools and therapies for management.”

The studio launched its first game, Open Spaces, this past fall after participating in Level Upstate, a summer accelerator program run by the Digital Gaming Hub at Rensselaer to help small teams commercialize their projects. The game, a visual novel about anxiety and agoraphobia, aims to help players who are living with a mental illness, as well as serve as an educational tool for the broader world. For those living with a mental illness, the goal is to help them identify ways they might be able to manage their symptoms.

Since mental health conditions can affect everyone differently, Open Spaces intentionally presents players with four very diverse characters living with anxiety and agoraphobia. By presenting characters that differ greatly in terms of gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and personal interests, it increases the chance that a player will be able to personally identify with a character and in turn, find techniques that help manage their symptoms. “Where games differ from other mediums is that they add in a layer of interactivity so it allows you to step into someone’s shoes a little more directly,” says Tess Wainwright ’16, lead narrative designer for the game and a graduate of the games and simulation arts and sciences program. “I said to myself, ‘These are the problems this person might deal with; what sort of characters can I build that exemplify that?’”

Understanding Cognitive Processes

Every year, thousands of classic video game fans head to Oregon for the Portland Retro Gaming Expo. Among them are some of the world’s greatest Tetris players, each determined to be crowned champion at the event’s Classic Tetris World Championship. Also present at the event is a group of cognitive scientists from Rensselaer who are leveraging Tetris, one of the most widely played games in the world, to gain insight into how humans learn and acquire expertise. “Tetris is really a dynamic decision-making task,” says Wayne Gray, a professor of cognitive science and leader of the research. “It’s a task where even doing nothing requires a decision to do nothing.”

After participants are done with the competition’s qualifying round, the team of researchers asks the “experts” to play just once more — this time, on special devices tracking all the interactions they have with the game. By tracking everything from how the players rotate the pieces to the adjustments they make to their speed, the researchers are able to identify patterns of behavior. The devices are even equipped with eye trackers, which provide an additional layer of insight into the non-physical interactions players have with the game, such as looking at the preview box. “The eyes really let us know what people are thinking about,” Gray says.

By comparing expert behavior to the data they’ve already collected from hundreds of novice players, the cognitive scientists hope to better understand how people learn and more importantly, identify a framework for acquiring expertise that could be used when it comes to perfecting other technical tasks. While the research, funded by the Office of Naval Research, may not transfer directly to other fields, a better understanding of expertise is something that could be applied widely. “Laparoscopic surgery is one example,” he says. “If we could do the same with surgeons as we are doing with Tetris players, we may be able to come up with better prescriptions for medical training and different ways of doing medical procedures.”