Venture Forth

Delivering life-saving research from the lab to the marketplace

By Jodi Ackerman Frank

Medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and modern conveniences such as email and virtual assistants didn’t happen overnight. They all began with an idea. And with curiosity and research, the idea eventually became a patented product in the marketplace. On the Rensselaer campus, researchers are nurturing their ideas from discovery to innovation to ultimately bring hope to millions and, in some way, make the world a better place.

For Juergen Hahn, who heads the Biomedical Engineering Department, his work will one day give answers to parents who are desperate to help their children. Today, there are 3.5 million kids living with autism. Most children are diagnosed around age 4, based on behavior and development. By this time, they have missed earlier interventions that could have improved their ability to function and have a higher quality of life.

About five years ago, Hahn, whose research involves developing algorithms to discover metabolic patterns and biological processes underlying autoimmune and other inflammation-related conditions, decided to study autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

“When I looked at the work being done in this area, I found the type of approaches and algorithms we developed were not as widely done,” he says. “Our understanding of this disorder is still in its infancy, even though the prevalence is high and growing. So I saw that, clearly, there is a big need and also quite a bit of opportunity to shift our work into this field.”

Hahn wanted to apply his computational classification and modeling techniques to accelerate ASD research and make a difference in the lives of children with ASD and their families. In 2019, he developed the framework for the first blood test to diagnose the disorder, opening the door to earlier diagnosis and therapeutic development.

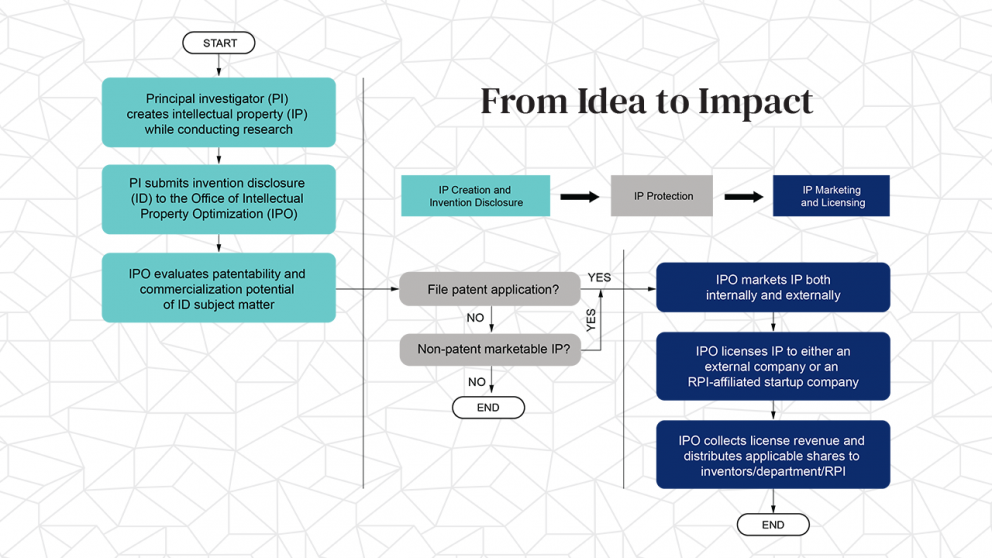

Realizing that his work could benefit countless children and families, Hahn contacted the Rensselaer Office of Intellectual Property Optimization (IPO) to patent the ASD blood test. In turn, the IPO found a corporate sponsor to take the technology to the next level. The intellectual property (IP) has now been licensed to BioROSA Technologies, a startup backed by SOSV, a global venture capital firm led by Sean O’Sullivan ’85. BioROSA will develop Hahn’s research results into a simple, accurate test that can be used in a doctor’s office.

“I was extremely interested to read of Juergen Hahn’s research in an issue of Rensselaer magazine and I reached out to him to encourage him to commercialize the idea,” O’Sullivan says. “Now BioROSA exists, with a practical process and business model that, within two or three years, could provide millions of parents with a very useful indication long before it would otherwise be possible.

“It’s gratifying to see research hit the ground running and get into the hands of the general population,” says O’Sullivan, whose son has autism. “There is a desperate need to address this issue of autism. The sooner the condition is diagnosed, the sooner more can be done with diet, probiotics, and some therapies to try to shift the course of the condition.”

“Juergen Hahn is a great example of how we collaborate with researchers across campus to protect their intellectual property,” says IPO Executive Director Bruce Hunter. “We help them move their innovations from the developmental stages to directly benefit society.”

Hahn has gained a deeper appreciation for IP protection. “We realized that no one is going to invest in developing a test procedure if the IP cannot be protected,” Hahn says. “That is why we filed for a patent — we want to see our results commercialized and give parents answers.”

Commercializing To Make a Difference

Like Hahn, Robert Linhardt is well aware of the immediacy that research can have, even after years of effort. Conventional heparin is extracted largely by purifying pig and cow intestines. When contaminated heparin killed 81 people and sickened hundreds more in 2007-08, Linhardt worked with a team of scientists from academia and industry to trace the contaminant. They found the culprit — a complex carbohydrate nearly identical in structure to heparin. The drug compound, sourced from China, had been introduced in the supply chain as a cheaper alternative. The crisis fueled a heightened sense of urgency for a safer alternative.

Three years earlier, Linhardt, the Ann and John H. Broadbent Jr. ’59 Senior Constellation Professor of Biocatalysis and Metabolic Engineering, bioengineered a synthetic heparin using sugars and enzymes found in the human body. “We built heparin from scratch, with no foreign material present, to ensure that we know exactly what is in the drug and have complete control over its ingredients,” says Linhardt, who is also the co-director of the Rensselaer Heparin Applied Research Center.

Linhardt, who holds more than 50 patents, began looking for opportunities to scale up and commercialize his synthetic heparin. Working with the IPO office, he recently secured a corporate sponsor to help move the new heparin into the final stages of product development. “The appropriate corporate sponsor is critical for advancing a new medical technology into the marketplace,” he says. “We’re always looking for opportunities to make a difference. The main motivation is to get the product out into the marketplace, and to the physicians and patients who critically need it.”

Biomedical imaging expert Ge Wang has focused on developing approaches to improve medical images in order to deepen understanding of diseases, and improve diagnosis and treatment. Wang, the Clark and Crossan Endowed Chair of Biomedical Engineering, feels working through the IP process is a critical component of promoting innovation and generating real societal impact. Wang, who holds numerous patents, says, “For me, commercialization or creating a startup are just not my priorities but I do appreciate and understand how these IP agreements and protections are important for the university and for industry.” Wang’s IP has been licensed by companies such as GE, making a life-saving difference for patients needing faster, more accurate disease diagnosis.

Early in his career, Eric Ledet worked as a biomedical engineer at the University of Arizona Cancer Center, where he collaborated with physicists, mechanical and electrical engineers, and oncologists to battle tumors using ultrasound technologies.

“I worked with doctors whose patients had end-stage illnesses and were in desperate need of solutions, so what we were developing went directly from the lab to serve them,” Ledet says. “There were no other alternatives for these patients.”

After earning his master’s degree, Ledet headed Albany Medical College’s research program in orthopedic surgery for nine years while finishing his Ph.D. in biomedical engineering. Today, he is a professor and head of the Rensselaer Innovative Medical Devices Laboratory, or the iMD Lab, where his students do research intended to rapidly provide medical solutions.

“We do translational research with the purpose of developing innovative, but simple solutions,” Ledet says. “We’re not looking to come up with answers to problems 20 or 30 years from now, but more within a three-to-five-year timeline.”

He teaches courses in product development and design to undergraduates and a new course in translation of biotechnology from bench to bedside to graduate students. Ledet solicits problems and needs from orthopedic clinicians, therapists, and care providers from across the country — even his own dentist — to provide meaningful experiences for student teams.

In recent years, the lab has partnered with the Center for Disability Services, for which students have developed much-needed technologies such as a patent-pending toothbrush that gives care providers a simpler way to brush the teeth of those who can’t do it themselves.

“Oral hygiene is important for health, nutrition, and also for social purposes, but it’s fairly difficult using a traditional toothbrush to brush the teeth of an individual who has physical or cognitive impairments,” Ledet says. “So, students engineered one for this purpose.”

Intellectual Property Matters

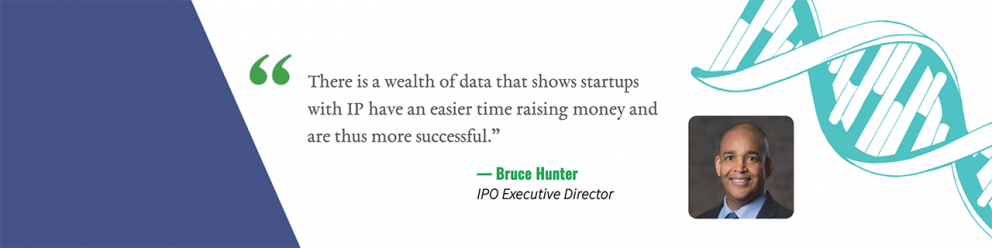

Hunter advocates the importance of IP. “There is a wealth of data that shows startups with IP have an easier time raising money and are thus more successful. While my past experience was as an entrepreneur, I have quickly learned how important a robust IP portfolio is to an academic institution,” he says.

“Researchers and the IPO having a strong and ongoing dialogue is of vital importance to Rensselaer,” Hunter explains. “As we build relationships with our researchers, we are also protecting intellectual property and maximizing opportunities to market IP. This often results in significant licensing opportunities of value to the researchers and Rensselaer, and of great benefit to consumers.”

Since leading the Intellectual Property Office, Hunter has streamlined the discovery process for early stage IP, and invention disclosure submissions with commercialization potential have increased significantly.

Jonathan Dordick, the Howard P. Isermann Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering, specializes in enzyme research for drug discovery, enzymes as therapeutic candidates, and disease diagnostics. Dordick has more than 45 patents, including as a co-inventor of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) detection method with Linhardt. In the 1990s, he founded EnzyMed, a pharmaceutical research company acquired by Albany Molecular Research.

“Creating useful IP provides great opportunities for both students and faculty, and Rensselaer as a whole,” Dordick says. “Students learn their ideas can play an important role in generating products that can impact society, and in the process, they gain valuable experience that often leads to more opportunities and perhaps some financial gain. There’s also the opportunity of playing a major role in starting up a company.”

As Dordick continues to add patents and explore new research opportunities, he involves his students, many of whom are listed as co-inventors on his patents, and actively encourages them to be inventive. “Students are critically involved. Even if I conceive a large amount of the technology, they are likely going to be making modifications or discovering something else in the process of their work,” he says.

All of which add up to economic value while tackling disease and enhancing health care for everyone. While the IPO has worked closely with researchers whose IP advances human health, the office also works with researchers and IP across all disciplines.

“Rensselaer has a long and storied history in developing so many practical and innovative technologies,” Hunter says. “As that tradition expands in the health-care field in particular, we will continue to work with our researchers to develop and commercialize intellectual property, add to the regional economy, and make deeply rewarding contributions to the larger community.”

Related:

-

Video — “What is IP?”